For Part 1 of this post on student surveys and PQA, click here.

How can we get lots of repetition on hi-frequency language, so that the students develop a practical Hebrew foundation? Here are some ideas for after you take an oral survey of student interest, such as ‘Which ice cream do you love?’ (See an extensive Hebrew menu of ice cream flavors here.)

Layer on a Visual Anchor:

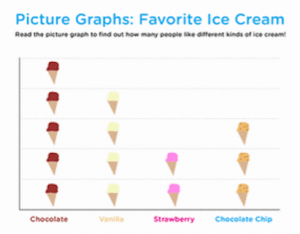

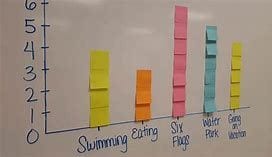

When we casually ask the same question to each class member and orally collect personalized survey information, massaging it into a compelling conversation, we can later insert this new-found information into a graphic organizer. This allows us to focus on a visual anchor as we review the community’s preferences, and since we’re doing it with a new visual, it feels fresh and novel.

Simple visual aids may include:

- A labeled T-chart

- a bar graph

- a tally chart

- a simple list

We can easily draw this on the white board at the front of the room. We can get fancy, adding colorful artwork, borders, graphics, etc.

Then, we review and discuss (same or next class) based on that class-specific visual. No extra work for teacher – we build the graphic in real time or after the initial conversation. We may need to think through what we’ll want the info graphic to look like, and prepare, print or draw a template.

We may also choose to create a paper template, so that each student can track the data as it’s collected – but wait to do this until after the students demonstrate a secure foundation in basic Hebrew – several hours/months into the school year.

By the end of this session of circling, interviewing and asking details using repetitive language, comparing and contrasting preferences, restating and re-telling in slightly different phrasing (“They love; they do not love”), and presenting the data visually in a graphic organizer, you’ll be ready to add some new questions to the mix.

How many students love Tutti-Frutti?

How many girls love ice cream that has chocolate?

NB: Make sure the ?כמה interrogative poster from my Hebrew Corpus Word Wall is posted for Pause-Point-Slow.

Another easy visual way to anchor a survey discussion is via a slideshow – in this case various internet images of different ice cream flavors. (Requires projector and screen). Simply narrate your way through the slides, asking questions and making comments as you flip through.

Experiment with different formats, beginning with those that seem easiest for you to execute, allowing you and the class to remain comprehensible and interesting.

Literacy Extensions:

*To practice writing their names while creating a simple bar graph, have each student write/copy his/her Hebrew name (from a prepared slide or chart) on a sticky note and ‘vote’ in the appropriate survey column. (In this case the column titles will be preferred flavors of ice cream.)

*Create a brief reading on the board in real time by writing sentences from the discussion and model reading them aloud. Ask students to join in if they want, otherwise visually track the words as you read.

*Write up a ‘class story’ – a series of patterned statements based on the conversation – and a sentence about each student -and read it to the class.

Kids of many ages (not just the youngest!) love to illustrate their class story page – experiment with giving a few minutes/crayons to do this – the resulting ‘book’ is a lot more inviting to read.

Writing/Dictation:

*Point to written class list of students’ names – this is good to have on chart paper for all to see and decode throughout the year.

Do target language dictations on dry erase boards, (lowers anxiety), one sentence at a time. We want sound and meaning already in their heads when they come to a writing/reading task. Let’s say we want to dictate these 3 sentences:

1. Alisa loves Moose Tracks ice cream. .עליזה אוהבת גלידת מוס טרקס

2. Talia has an allergy to chocolate. .לטליה יש אלרגיה לשוקולד

3. Gavriel loves Mint Chip. .גבריאל אוהב גלידת שוקולד מנטה

The purpose of dictation, for our setting:

- Associating sound and meaning to the letters/ written word

- Hebrew cursive letter formation (muscle memory)

- Building student confidence

Follow the dictation protocol below, keeping dictated sentences short and simple to guarantee student success.

Before starting, briefly discuss behavioral expectations regarding dry erase board/materials use.

For example:

We respect these materials, insuring that they can be used again and again by:

- not tapping, scratching, doodling, throwing, etc.

- demonstrating we understand my instructions

Back to the task:

Students write the one sentence they hear on lined side of dry erase board.

Hebrew alphabet poster -block and manuscript letters -at front of room.

Teacher repeats the sentence aloud as requested.

Teacher circulates and notices non-standard inventive spelling/letter formation. It’s OK! Spelling emerges over time from reading. It probably won’t be accurate to start. Resist your impulse to correct student work!

After students have attempted to write it, teacher models/writes correct sentence in large cursive print on the board. Students are noticing how you form your letters, so write big, slowly and clearly here. We give them a minute to compare their version with yours, noticing differences, then students copy the correct version below their initial attempt. Afterwards they may erase, or if they want and there’s room, go on to another dictated comprehensible sentence.

Briefly point out ‘final letters’ in Hebrew, or other surface features.

Students look at the 2 versions, then erase or continue same protocol for next sentence.

See my related blog post: https://cmovan.edublogs.org/2016/09/22/demystifying-hebrew-literacy-part-1/

Practice Hebrew classroom survival phrases by having students follow your commands:

- pick up/put down boards/markers

- uncap/close markers

- write/ erase

By laying in these instructions, you insure that you can conduct subsequent dictation activities entirely in Hebrew. All repeated class routines, such as materials distribution and collection, are worthy of laying in in the target language, since they will come up over and over again. Materials management is a great way to provide concrete language and allow students to demonstrate their understanding with a performance task.

Read about Classroom Hebrew survival phrases here:

https://cmovan.edublogs.org/2017/03/21/survival-for-the-comprehensible-hebrew-classroom/

and find my Classroom Survival Expressions when you scroll down on the Hebrew Corpus.

Teach, write, establish meaning and point to the Hebrew words, “Please repeat/Again” so that students can self-advocate whenever necessary.

I recommend not sacrificing more than 5-7 minutes at the end of CI class time for dictation. It serves as a brain break & alternative literacy activity, and to help develop recognition of the letters and their formation, but focus on your primary goal of driving acquisition by providing a flood of compelling, comprehensible input.

Everything I learned about Dictation, before trying it and tweaking it in my own elementary classroom, I learned from master CI French instructor, Ben Slavic. See his Dicteé protocol, here.

Summary Of T/CI-Aligned Practices:

Summary Of T/CI-Aligned Practices:

All this personalized surveying at the beginning of the school year and throughout, serves several crucial purposes in the Comprehensible Input framework:

- Provides lots of connected, compelling, tailored Comprehensible Input at the discourse level

- Provides massed exposure through repetition of hi-frequency practical language

- Slowly builds students’ stamina for processing conversational /discourse-level Ivrit

- Builds a community that is warm & playful, where each individual feels known and therefore safe

- Establishes class norms and behaviors, by pointing them out/modeling norms if/when there are infractions

- Sends a strong message that in this class, we communicate primarily in Hebrew – that you understand – to build our Hebrew skills

Caveat On Survey Questions:

We want interesting info without being too personal or potentially sensitive (asking abt parents if there is divorce; asking about a pet when someone’s dog just died, etc.)

SOME SAFE TOPICS FOR INTEREST SURVEYS:

(Advise older students that only vetted and appropriate topics will be included in this class)

-Favorite ice cream flavor ‘Which ice cream do you love?’, fruit, etc.

-Favorite childhood picture book

-Do you have a pet/ pet name – non pet owners can pick a dream pet (including fantasy pets – here we offer cognates like dragon, flamingo, gorilla, etc.)

-TV – possibilities are endless but must be appropriate – train your Ss to suggest only ideas appropriate for a the setting – no violence, romance, swearing, etc.

-Least/favorite – restaurant; chores; vegetables

-(Least)/favorite book/movie; or character (or any art form)

-(Least)/favorite place to hang out (specific) other than school

-(Least)/favorite music type/song/artist

-Dream vacation – where (specific)?

-Is your room neat or messy? ?החדר שלך מסודר או יש בלאגן

-Secret talent

-Secret fear (all secrets can be invented – this is Hebrew class – where anything is possible!)

Again, we the teacher are very interested in our students’ answers, we are teaching to the eyes, spinning the conversation out of the (sometimes fantasy) ‘facts’ we are collecting – comparing and contrasting – extending the language and getting lots of repetition; recording the info visually and/or in writing – via info graphic and/or a class story.

Here is another survey questionairre you may be able to use – click on “See Inside” above the graphic.

https://teachables.scholastic.com/teachables/books/Student-Interest-Survey-9780439303026_028.html

Whew. A lot to think about at first. How much language? When to establish meaning by writing on the board? How often to circle, and which parts? (Go for the verb-containing chunk!) You will try it, and it will get easier. Like the language itself, you’ll begin to acquire some practices with automaticity, freeing up your brain space for other concerns. Your skills will grow!! The main thing is to get started, give it a try, and watch your students bask and thrive in a warm pool of compelling, comprehensible input!

*Terry Waltz, PhD. See Hebrew ‘Super 7’ verbs here – scroll down to page 15.

End class with a predictable exit routine. In my Spanish class, I adopted this courteous call & response from master Comprehensible Input teacher,

End class with a predictable exit routine. In my Spanish class, I adopted this courteous call & response from master Comprehensible Input teacher,