As usual, this past Wednesday I wasn’t sure where my Hebrew classes would take me. Where would our conversation meander, with my prompting and guidance, and what hi-frequency language could I wrangle from it? I knew we needed to keep playing with the hi-frequency language we’d used thus far, and I was wary to start introducing more new words. The previous (Sunday) Hebrew class was so short – I teach three consecutive 20-minute classes – and with transition and settling time, the kids barely get 12-15 minutes of Hebrew instruction. Wednesday’s 35-minute classes are the heart of the program.

I knew we needed to keep playing with the hi-frequency language we’d used thus far, and I was wary to start introducing more new words. The previous (Sunday) Hebrew class was so short – I teach three consecutive 20-minute classes – and with transition and settling time, the kids barely get 12-15 minutes of Hebrew instruction. Wednesday’s 35-minute classes are the heart of the program.

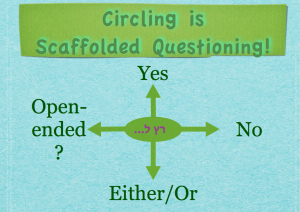

I loosely planned to continue with our (cognate-filled) animal story from the previous week. I’d surveyed the kids about their pets while circling doesn’t/have, goes and wants ( יש, אין, הולך, רוצה).*

Then I sent a pet-seeking volunteer to various pet stores (location posters) around the room, where the shopkeeper (classmate) offered a gorilla, flamingo, zebra, or giraffe. I was willing to see where the story would go, prepared to layer on a new hi-frequency structure or two, as necessary (i.e., takes it home; buys it; says to – לוקח הביתה, קונה, אומר ל).

The best laid plans….

Wednesday was a rainy, gloomy evening, and the Chicago Cubs had just lost Game 1 of the World Series, 6-0, the night before. The kids looked tired when they entered the Hebrew room. I asked some icebreaker questions with charades-like gesturing: Are you hungry? Are you sad? Are you tired? Presto! The majority of the kids were understandably exhausted, having been up late the night before watching the Cubs’ drubbing. I promptly wrote: אני עייפה, אני עייף and their translation, I’m tired, on the board. One of the teachers offered, אני ממש עייפה – ‘I’m REALLY tired!’ and after we established the meaning of the phrase, several boys and girls agreed: ‘!אני ממש עייף!’ ‘אני ממש עייפה’

Being the conscientious professional that I am, I did as any self-respecting Jewish Mother-turned Hebrew School teacher would. I offered them a nice nap. Right then and there. ‘?את/אתה רוצה לישון’ ‘Do you want to sleep?’ One volunteer ‘slept’ on a bed made of 3 class chairs lined up side by side, while his bunkmate slumbered beneath. A girl snored loudly under a table in the corner, as did a boy on the opposite side of the classroom. Yet another student sprawled out under her seat. We (remaining & awake audience members) checked on each of our nappers. ‘Is s/he tired? Is s/he sleeping? Wow! S/he’s really sleeping! S/he’s really tired!’ I called up assistants to gently awaken the nappers. We tried coaxing our sleepers to their feet with soft whispers, light tickling and improvised songs (I led a בוקר טוב = Good Morning song to the tune of, “If You’re Happy and You Know It”). A girl in one class suggested we tickle our sleepers with my rubber lettuce leaf -סלט – under their noses. It worked! We continued around the room playing with each sleeping kid, mirthfully attempting to wake them while getting tons of repetitions on phrases such as, ‘S/he’s sleeping; s/he wants to sleep; s/he is tired.’ Finally, as time ran out, we reached consensus on an appropriate alarm clock sound, and woke our slumberers with a choral sound effect: Beeeeeeeps, rrrrrinnnngs, and one class decided on a continuous loop of, “!קום בבקשה” – ‘Get up, please!’

Our scene went absolutely NOWHERE. The initial query, “Are you tired?” set the docket for the rest of class. We simply and gleefully played with the unlikely possibility of taking a teacher-sanctioned nap in Hebrew class. We explored each actor’s interpretation, one after the next, affording lots of silliness, laughter, and compelling repetition.

Our scene went absolutely NOWHERE. The initial query, “Are you tired?” set the docket for the rest of class. We simply and gleefully played with the unlikely possibility of taking a teacher-sanctioned nap in Hebrew class. We explored each actor’s interpretation, one after the next, affording lots of silliness, laughter, and compelling repetition.

As Dr. Stephen Krashen, father of modern Second Language Acquisition theory says, “Language acquisition proceeds best when the input is not just comprehensible, but really interesting, even compelling; so interesting that you forget you are listening to or reading another language.”

I’ll bet most of the kids didn’t even realize, in the moment, that it was all happening in Hebrew.

*For more info on circling and other Teaching with Comprehensible Input foundational skills, check out these Powerpoint presentations: Reimagining Modern Hebrew Language Instruction and T/CI Foundational Skills, which are also on my blog homepage tabs, Intro to T/CI and Optimizing SLA, respectively.

Processing a new foreign language takes the brain even more time! So teaching youngsters a new language? Whoa! Slow it wayyyyyyy down. Fellow Canadian Comprehensible Input blogger Chris Stoltz offers this rule of thumb on

Processing a new foreign language takes the brain even more time! So teaching youngsters a new language? Whoa! Slow it wayyyyyyy down. Fellow Canadian Comprehensible Input blogger Chris Stoltz offers this rule of thumb on

Humans acquire languages one way only: By understanding messages, aka, Comprehensible Input (Krashen, Foreign Language Education The Easy Way).

Humans acquire languages one way only: By understanding messages, aka, Comprehensible Input (Krashen, Foreign Language Education The Easy Way). Our rich and diverse liturgical/lifecycle/holiday curricula – hereafter called religious school – explores prayers, songs, religious artifacts, images, communities (including Israel), food, customs, and some texts. Let’s discuss the texts.

Our rich and diverse liturgical/lifecycle/holiday curricula – hereafter called religious school – explores prayers, songs, religious artifacts, images, communities (including Israel), food, customs, and some texts. Let’s discuss the texts. as pre-schoolers (or even earlier these days!) with their native English.

as pre-schoolers (or even earlier these days!) with their native English. without simultaneously presenting their written Hebrew counterparts in context. But I’m not advocating for isolated word labelling, like we used to see in so many bilingual classrooms in the 80’s – 90’s. I’m talking about contextualized chunks of written Hebrew language, chunks that will be repeated orally throughout the normal course of class.

without simultaneously presenting their written Hebrew counterparts in context. But I’m not advocating for isolated word labelling, like we used to see in so many bilingual classrooms in the 80’s – 90’s. I’m talking about contextualized chunks of written Hebrew language, chunks that will be repeated orally throughout the normal course of class.