As we careen toward פסח and then to the end of another Hebrew school year, I’ve transitioned from my role as teacher trainer and lesson modeler, to coach and mentor. I enjoy observing and providing positive feedback to my colleagues as they experiment with their newly adopted teaching with comprehensible input (T/CI) strategies, and I continue to learn so much about how to support both our students’ Hebrew acquisition, and our teachers’ acquisition of the T/CI skills!

As we careen toward פסח and then to the end of another Hebrew school year, I’ve transitioned from my role as teacher trainer and lesson modeler, to coach and mentor. I enjoy observing and providing positive feedback to my colleagues as they experiment with their newly adopted teaching with comprehensible input (T/CI) strategies, and I continue to learn so much about how to support both our students’ Hebrew acquisition, and our teachers’ acquisition of the T/CI skills!

My coach/mentor comments after I observe a lesson focus on:

- What the teacher did to help her students feel welcome and comfortable (to keep the affective filter low, and optimize the environment for acquisition);

- How she made the Hebrew comprehensible, contextualized and compelling for her students.

One pattern I have found across observations is the need for a compilation of Survival Hebrew for the CI Classroom. We need to have Hebrew go-to phrases for general classroom management; materials distribution and collection; director’s cues for student actor dramatization, and more. Of course every time we try something new requiring instructions, we can make the Hebrew utterance comprehensible by establishing meaning (writing the Hebrew and it’s English counterpart clearly on the board, followed by gesturing and other extra-linguistic supports). Of key importance is maintaining the flow of input in Hebrew without constant English intrusion or code-switching (i.e., alternating between languages in the context of a single conversation).

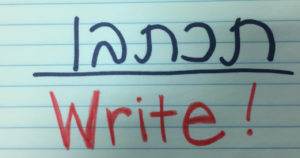

Incorporate the specific required ‘teacher talk’ only as the need arises. If, for example, you don’t use the dry erase boards, markers and erasers for the first say, 3 weeks of school, concentrating instead on flooding students with aural input, then when you do decide to bust out the materials, think through both the distribution/collection protocol (so that it’s efficient and repeatable) and the Hebrew you will use to operationalize the task. There are the names of the materials to consider, and also such imperatives as: Take, pass, put, give, open/close (the door/marker); draw, show, write, and erase, just to name a few! Practicing a subset of these commands in advance, a la Total Physical Response (TPR), is both a fun way to manipulate the materials as well as an effective form of comprehensible input. This year, I had my Hebrew students practice manipulating the materials according to my instructions for a few short minutes, every time we used them. (For a discussion on TPR, see this blogpost.) Many successful CI teachers have very particular protocols for materials management, allowing them to minimize interruptions & English usage, while maximizing target language input and enjoying a concrete demonstration of student comprehension.

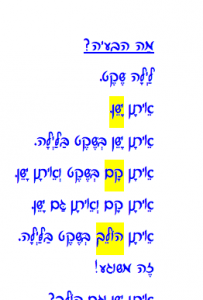

Here’s an example of using target language to manage materials distribution. Notice how I choose a simple way to express my wish, and then repeat the heck out of it, using individual students’ names, while they manipulate the materials. It feels kind of like kindergarten, only for our students, it’s more novel and challenging in a new language! I designate some passers (often people sitting at the end of the row) to distribute a row’s worth of boards, pens, or erasers to their neighbor, who then passes across the row. Materials are also collected row-at-a-time in this fashion. So to practice, I might say,

“Chaim, you give 5 boards/pens/erasers to Shira.

Shira, you take one board/pen/eraser and please give the boards/pens/erasers to Yoni.

Yoni, please take one board/pen/eraser and give the boards/pens/erasers to Ronit,” etc.

Hopefully, you can see how such narration and repetition during this ‘training’ phase also provides tons of contextualized comprehensible input! To spice it up, some teachers practice this (narrated or not!) distribution routine with a timer, and repeatedly try to beat their class’ best time.

I’ve added my Classroom Management and Survival Hebrew to the bottom of my Hebrew Corpus. It’s a go-to list for some of the survival Hebrew that might arise in your T/CI classroom. I invite you to respond to this post with suggestions for additional entries, as the list will be periodically updated. Please note that not all the classroom directions need be expressed in the ציווי or imperative tense. We can also express commands using the Hebrew infinitive, and in the indicative, as in, “Now you (the students) are drawing a giraffe.” We can sometimes change the ‘person’ when speaking to an individual (male or female) or the group, so long as we establish meaning, without grammar explanations, unless specifically asked (grammar explanation requests are rare among young learners). There are no rules about this, except that we don’t interrupt the flow of Hebrew by naming or explaining (in English) which tense/person we are using and why, or how the tenses/persons are formed, or how they compare to one another. We’re just going to say it; establish meaning (translate the Hebrew utterance by writing underneath in English); and when possible, add a gesture and/or use a prop to help support understanding. And don’t forget, for our novice learners we can choose to substitute an oral instruction for an extra-linguistic prompt, as in gestures & facial expressions, which can be combined with props, pictures and sketches.

and when possible, add a gesture and/or use a prop to help support understanding. And don’t forget, for our novice learners we can choose to substitute an oral instruction for an extra-linguistic prompt, as in gestures & facial expressions, which can be combined with props, pictures and sketches.

It’s my hope that having a handy list of common classroom management expressions to be introduced and used as needed will help keep our Hebrew comprehensible input train chugging happily along the rails!

I knew we needed to keep playing with the hi-frequency language we’d used thus far, and I was wary to start introducing more new words. The previous (Sunday) Hebrew class was so short – I teach three consecutive 20-minute classes – and with transition and settling time, the kids barely get 12-15 minutes of Hebrew instruction. Wednesday’s 35-minute classes are the heart of the program.

I knew we needed to keep playing with the hi-frequency language we’d used thus far, and I was wary to start introducing more new words. The previous (Sunday) Hebrew class was so short – I teach three consecutive 20-minute classes – and with transition and settling time, the kids barely get 12-15 minutes of Hebrew instruction. Wednesday’s 35-minute classes are the heart of the program.

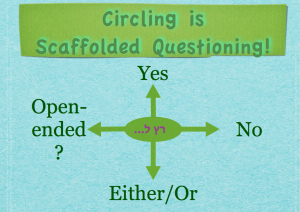

Our scene went absolutely NOWHERE. The initial query, “Are you tired?” set the docket for the rest of class. We simply and gleefully played with the unlikely possibility of taking a teacher-sanctioned nap in Hebrew class. We explored each actor’s interpretation, one after the next, affording lots of silliness, laughter, and compelling repetition.

Our scene went absolutely NOWHERE. The initial query, “Are you tired?” set the docket for the rest of class. We simply and gleefully played with the unlikely possibility of taking a teacher-sanctioned nap in Hebrew class. We explored each actor’s interpretation, one after the next, affording lots of silliness, laughter, and compelling repetition. To most American English speakers, languages written in non-Romanized letters seem impossibly difficult. Their very unfamiliarity is off-putting at the least, and constitutes a deal-breaker for many. “How can I possibly learn….? (Fill in the blank: Hebrew, Mandarin, Arabic, Russian, etc.) The writing is downright indecipherable!”

To most American English speakers, languages written in non-Romanized letters seem impossibly difficult. Their very unfamiliarity is off-putting at the least, and constitutes a deal-breaker for many. “How can I possibly learn….? (Fill in the blank: Hebrew, Mandarin, Arabic, Russian, etc.) The writing is downright indecipherable!”

Stand up.

Stand up.

I wanted our kids to walk away feeling encouraged. And successful. And smiling. Those were my ‘curricular goals’ from which I decided to backwards-plan. No worries about hi-frequency structures, circling, repetitions, or the like… yet. Just a fun, informal meeting & intro with some back-and-forth Hebrew communication.

I wanted our kids to walk away feeling encouraged. And successful. And smiling. Those were my ‘curricular goals’ from which I decided to backwards-plan. No worries about hi-frequency structures, circling, repetitions, or the like… yet. Just a fun, informal meeting & intro with some back-and-forth Hebrew communication.

End class with a predictable exit routine. In my Spanish class, I adopted this courteous call & response from master Comprehensible Input teacher,

End class with a predictable exit routine. In my Spanish class, I adopted this courteous call & response from master Comprehensible Input teacher,