Recently, as I was observing some of the teachers whom I’ve begun to train in CI strategies, I was struck by how our issues in Hebrew school environments are generally the same as those of any World Language instructors, with the exception of a few pesky details:

Recently, as I was observing some of the teachers whom I’ve begun to train in CI strategies, I was struck by how our issues in Hebrew school environments are generally the same as those of any World Language instructors, with the exception of a few pesky details:

•Hebrew reads from right to left and doesn’t employ the Romanized alphabet (like Spanish or French, for example), making it less ‘transparent’ and harder to decode for the English-dominant learner;

•Hebrew texts – textbooks for learners, religious texts, children’s books, newspapers, etc.- are printed in square-edged block, yet most Hebrew teachers (and speakers) hand-write using flowy-er cursive;

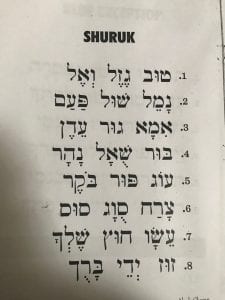

•Many traditional teachers and Hebrew instructional texts include vowel pointing, called ‘nikkud,’ but proficient Hebrew speakers do not use nikkud in their writing, nor need it for reading.

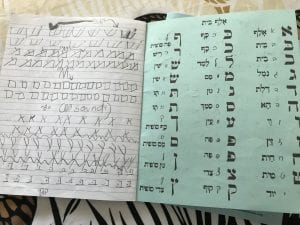

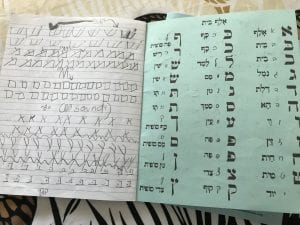

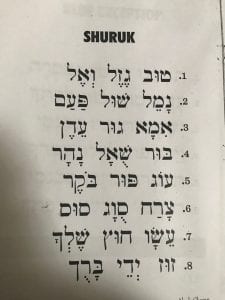

These clunky realities regarding written Hebrew have conspired to preserve outmoded ‘isolate & copy’ exercises that even my parents (and theirs?) suffered through at least a generation ago…. in favor of more engaging and meaningful learning experiences for our students.

Raise your hand if you had a (light blue?) lined mach’beret in which you dutifully copied the isolated Hebrew ‘letter/s of the day’ over and over, this time with a kamatz, this time with a segol….

Or maybe you learned to decode with a primer. On the third or fourth line of the page, the target letter was combined with another to form a sound chunk, or phoneme. Perhaps half-way down the page the gimmel in question was clumped with two or three other Hebrew letters, to form a nonsense word, or even a real one, whose meaning, unknown and without context, sounded equally befuddling!

This is how we did it, baby. Squiggles and dots on the page, without a schema for sound, and utterly devoid of meaning.

But Second Language Acquisition reminds us that the durable linguistic foundation is built on compelling and meaning-bearing auditory input. We need a sense of what is being expressed, and we need to develop, through exposure, an ear for how it sounds, in order to extract a message. Input precedes output, as sure as listening comprehension precedes reading.

So, back to the practical classroom question:

How can we help crack the written Hebrew code early on, clearing obstacles so our students can access the power of reading?

We need a way to get our students reading in the target language ASAP without overwhelming them, to bolster and broaden their input, reinforcing and extending the language they’ve been taking in aurally.

I say we begin to resolve this conundrum with the most personalized and intriguing bite-sized input available from Day One: The students’ Hebrew names.

Some students have been together before, and know each others’ Hebrew names. I’m not suggesting a simple round of, ‘Ari’eh, meet Rami;’ ‘Liora, meet Ester.’ I’m recommending exploiting the Hebrew class roll as compelling yet narrow language, to flood the students with comprehensible auditory and written input. This readily available resource, I believe, can provide the contextualized exposure, repetition, and interest to break the code, flex the decoding muscle, and build confidence, all with a friendly & light-hearted community-building vibe.

Our task is to capitalize on our students’ names, which echo through generations of family history, to help our students recognize the letters, sounds and contours of these new Hebrew words. How can we harness the power of a name – likely one of the first words our students ever read or wrote in their native language, to jumpstart Hebrew literacy?

It’s simple. More PERSONALIZED QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS (PQA) – purposefully combined with literacy.

Here’s the scenario. The teacher has, in advance, a class list of the students’ Hebrew first names.

S/he copies it, in cursive Hebrew (NO VOWELS), onto poster-size chart paper, making sure the font is large/bold, consistent and legible from the back row of seats. There’s plenty of space between names (2 columns is fine); consider alternating colors for enhanced legibility.

The teacher posts the entire class list (possibly several sheets) onto the central teaching board.

The Aleph Bet Chart is also posted and visible.

The teacher initially engages in predictable circling, including Pause-Point & S-L-O-W (PPS).

All questioning occurs in the target language, using the interrogative word posters from the adjacent Word Wall, as necessary (with PPS). Ideally, the students are somewhat familiar with their names and already have seen their name cards or name tags.

[To read more about Hebrew names and name tags, click here.]

Phase 1: Identifying Students By Name would work to kick off the year’s first day/s lesson/s.

ALL TEACHER BANTER IN HEBREW; students may respond in English (thereby demonstrating comprehension of the Hebrew message); Teacher points to relevant interrogative poster/s throughout the interactions.

T: Where [poster] is Yosi [pointing to first name on chart]?

T: Are you [pointing to student] Yosi? S: No.

T: You’re not Yosi…Hmmm. [Approaches a different student, points] Are you Yosi? S: No.

T: Oh, you’re not Yosi [pointing to student A], and you’re not Yosi [pointing to student B]. Hmm…Where [poster] is Yosi?

[returns to chart; points to the word, “Yosi”].

Students raises hand. Teacher approaches student.

T: (Surprised) Are you [pointing to student] Yosi? [Pointing to name on chart] S: Yes.

T: Ahh, class, he’s Yosi! [Points’ to student, then name on chart] He….is….Yosi!

Teacher applauds, encouraging others to applause for figuring it out. Teacher continues with another student, pointing first to the chart, modeling the decoding, and trying to find/match the name of the student in question using similar banter. As each student is identified, s/he celebrates, then groups them next to each other, affording movement and a ‘shuffling the deck’ challenge.

Remember: Students may answer teacher questions in English; the focus, at this early stage, is on demonstrating comprehension, not on Hebrew output.

Since it’s already October and we know our students’ names, we might skip Phase 1 and move straight to…

Phase 2: Simple Name-Focused Personalized Questions & Answers (PQA)

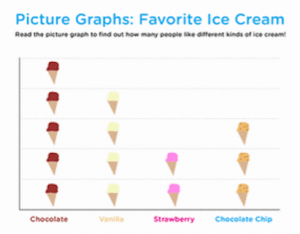

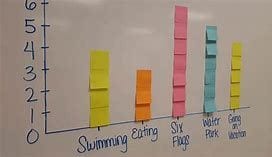

With the Hebrew class names chart front-and-center, decide upon a compelling survey question or two. In my last series of posts we focused on favorite ice cream flavor, which lent itself, in the heat of the waning summer, to some pleasantly compelling & comprehensible banter. Then we followed with sample literacy extensions, creating a simple data table to record the class info, and used it to review, count, compare, contrast and draw conclusions, all while staying narrow and in-bounds with the language in use. Such T-charts and bar graphs also employ student names and cognate ice cream flavors, and therefore serve as appropriately contextualized, and heavily scaffolded Hebrew literacy experiences! Students are invited to decode & comprehend (i.e., READ!) the limited Hebrew text, recognizing letters and generalizing their sounds in context. In this way, written input is predictable, building success and confidence!

With the Hebrew class names chart front-and-center, decide upon a compelling survey question or two. In my last series of posts we focused on favorite ice cream flavor, which lent itself, in the heat of the waning summer, to some pleasantly compelling & comprehensible banter. Then we followed with sample literacy extensions, creating a simple data table to record the class info, and used it to review, count, compare, contrast and draw conclusions, all while staying narrow and in-bounds with the language in use. Such T-charts and bar graphs also employ student names and cognate ice cream flavors, and therefore serve as appropriately contextualized, and heavily scaffolded Hebrew literacy experiences! Students are invited to decode & comprehend (i.e., READ!) the limited Hebrew text, recognizing letters and generalizing their sounds in context. In this way, written input is predictable, building success and confidence!

Say this time we mine another universally popular topic of convo, pets. Who has a dog? Who has a cat? We can set up the topic, building a bridge of interest, and scaffolding meaning by first showing and comprehensibly ‘talking through’ a brief slideshow of, say, 5 funny cartoon animals: a dog, cat, kangaroo, flamingo & llama (the latter three are words borrowed directly into Hebrew). If possible, also print these pictures, and have them posted to refer to in class.

For students who don’t currently own a pet, you’ve already, by including the three cognate animals above, introduced the possibility of owning a fantasy pet. Tell them to pick one they like, and stick with it. Draw from a broader list of Hebrew cognate animals, (scroll down!) the more outrageous, the better. List a few fantasy choices in Hebrew on the board, and add the real pets to this short list as they are claimed by students.

Notice that among these three animal cognates alone, קנגורו, פלמנגו, למה the students will have in-context exposure to nine distinct Hebrew letters/sounds! Add dog & cat – כלב, חתול – and that’s more than half the Alef Bet.

CAVEAT: You may choose to Hebrew label these cognate fantasy animals, though since you will be saying their identical-to-English names while pointing to the picture, it’s not necessary, and too much text could overwhelm the absolute novice.

Remember: We want reading to feel automatic and effortless, so we can front load sound and meaning, and wait to attach reading later.

In this version of PQA, the phrasing of the personalized question often begins with, “Who?” because we want the students to successfully answer our questions with their classmates’ Hebrew name. We are asking them to repeatedly associate the sound of their classmate’s name with its written counterpart (on the name chart).

As the information is initially collected, the teacher, as usual, is working the crowd. S/He is circulating, ‘teaching to the eyes’ (Susie Gross), ascertaining, confirming, misunderstanding, negating, affirming, comparing (with self and other student/s), grouping, counting, restating and summarizing. As every name arises, she is Pause-Point-S-L-O-W-ly (PPS) drawing attention to the student’s name from the central name poster/s.

Say we asked, “Who has a kangaroo?” and learned that, in fact, Sagit does.

T: Nofar (PPS), Sagit (PPS) has a kangaroo (PPS). Do you (points to Nofar (PPS)) have a kangaroo? (PPS)

S: No.

T: Oh, Nofar (PPS), you don’t have a kangaroo…Nofar, do you have a dog? (PPS)

S: Yes.

T: Nofar (PPS), you have a dog! (PPS) Class, Nofar (PPS) has a dog! (PPS)

Note that the teacher is free to pepper Yes/No and Either/Or questions, which work well when the answers are animals (‘dog’ & ‘cat’ would need to be listed/translated on the board) or kangaroo, etc. Here, s/he is Pause-Point-S-L-O-Wly indicating the animal type from the posted Hebrew words/pet pictures. Our mission is to converse comprehensibly at the discourse level (back and forth in meaning-filled chunks) while attaching the written code to the sounds our students are hearing.

Sound + Meaning… Then Add Reading.

T: [Confused] Class, Sagit (PPS) has a kangaroo (PPS), or Sagit has a dog (PPS)?

Ss: Dog (PPS).

T: Ah, Sagit (PPS) has a dog?

Ss: Yes (PPS).

[Teacher points to previously modeled Yes/No Hebrew poster.]

T: Who (PPS) has a flamingo (PPS)?

S: Ze’ev (PPS).

T: Ahhh, so Sagit (PPS) has a kangaroo (PPS); Nofar (PPS) has a dog (PPS); and Ze’ev (PPS) has a flamingo (PPS)?

Ss: Yes! (PPS)

T: Fantastic!

Phase 3: Follow-up: Creating a Literacy-Rich Visual Anchor

We can interview all the students in the class in one go (though it’s a lot to process for the absolute novice reader – so monitor for attention/fatigue), then project or post a simple three-column (Hebrew) chart: Student’s Name; Student’s Hebrew Name; Student’s Pet. In our parallel T/CI universe, everyone has a pet, even if it’s a gorilla:} The teacher can then re-ask the information with new purpose, this time filling in the missing info.

It may feel repetitive to you, teacher, but if you approach the info as fascinating, and the chart as a task worthy of the class’ time, then the novelty of the chart will feel fresh, and the students will follow your lead, this time guided by reading input. Oh, andfFeel free to draw quick but discernible stick figure or cartoon like icons on the chart!

Students are noticing letter formation as the teacher fills in the information, so exploit the opportunity for the students to watch you write in Hebrew, emphasizing sound/letter correspondence aloud. Not the name of the letter, but the sound it makes within the word. After you finish writing the word (student name or pet); review the info yet again: (In Hebrew), ‘Ze’ev (PPS) has a flamingo.’ (PPS)

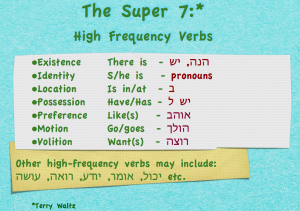

Perhaps in the teacher’s mind, one purpose of this CONVERSATION is writing and repeatedly reading students’ names & pets in order to, as we said above, lay in some foundational Hebrew literacy skills. However, in the course of the conversation we are also contextually exercising the heck out of the high frequency verb, “has/have” and its (completely different) negation, not to mention the essential Hebrew pronouns (I, you, he/she; we; they, etc.) A series of simple, yet high-interest sentences, all with a similar format, “Student X has/doesn’t have a Y [pet],” provides many permutations of playful, in-bounds, novice-level discourse in Hebrew!

B-I-N-G-O!

If you have more class time, or another day, try distributing the dry erase board materials (also discussed in the blog post linked below) and ask the following kinds of sure success questions: Who has a flamingo? Does Ze’ev have a cat? Have Ss flash their boards with written answers – they can copy classmates’ names from the name chart for a quick comprehension check and peek into their developing letter/word formation. (The students copy the words from the posted class roster.)

And as a double extra credit one time only super bonus:}, model (on the board) a full sentence, such as, “I have a gorilla.” Have the students copy the ‘I have’ part, and allow them to choose and copy whichever fantasy animal suits their fancy, completing the written sentence on their boards.

Then, simply circulate and observe your students’ emerging Hebrew literacy…. This is a baseline for later comparison. Throughout the year you will notice fewer letter reversals, more automaticity, and growing confidence in writing for meaning… one name at a time.

That was pretty painless, no?

For more on this topic, please read my earlier blog post, Demystifying Hebrew Literacy.

Recently, as I was observing some of the teachers whom I’ve begun to train in CI strategies, I was struck by how our issues in Hebrew school environments are generally the same as those of any World Language instructors, with the exception of a few pesky details:

Recently, as I was observing some of the teachers whom I’ve begun to train in CI strategies, I was struck by how our issues in Hebrew school environments are generally the same as those of any World Language instructors, with the exception of a few pesky details:

With the Hebrew class names chart front-and-center, decide upon a compelling survey question or two. In my

With the Hebrew class names chart front-and-center, decide upon a compelling survey question or two. In my

Summary Of T/CI-Aligned Practices:

Summary Of T/CI-Aligned Practices:

Recall how I had the puppet visit two local eateries before ending up at the ubiquitous Costco, where he found the object of his gastronomical affections.

Recall how I had the puppet visit two local eateries before ending up at the ubiquitous Costco, where he found the object of his gastronomical affections. Before my first graders arrived, I posted an 8.5″ x 11″ poster of each of my three locales – the two local restaurants, and Costco – whose iconic photos I found on Google Images – in three distinct areas of my classroom.

Before my first graders arrived, I posted an 8.5″ x 11″ poster of each of my three locales – the two local restaurants, and Costco – whose iconic photos I found on Google Images – in three distinct areas of my classroom.

Finally, Guácala goes (drives his minivan?) to Costco (where all roads lead.) The kids love the very mention of Costco, and glaze over with memories of bite-size samples.

Finally, Guácala goes (drives his minivan?) to Costco (where all roads lead.) The kids love the very mention of Costco, and glaze over with memories of bite-size samples.

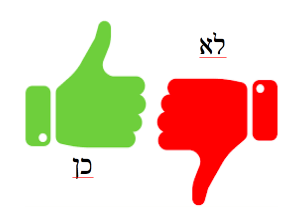

NOT STRESSED OUT or made to feel inadequate. A high affective filter can be a major obstacle to language acquisition, so we must be vigilant that we aren’t freaking out our kids, or they will tune out and turn off. And researchers will conclude that they are ‘losing their Hebrew language,’ when it’s really the program, itself, that has lost its way.

NOT STRESSED OUT or made to feel inadequate. A high affective filter can be a major obstacle to language acquisition, so we must be vigilant that we aren’t freaking out our kids, or they will tune out and turn off. And researchers will conclude that they are ‘losing their Hebrew language,’ when it’s really the program, itself, that has lost its way.

But they are, regrettably, also killing student (and teacher) interest and engagement, because the set curriculum is…OK I’ll say it: mind-numbingly boring. Set curricula often ‘covers’ static and humorless topics about which the students are not interested or passionate; nor do many of the themes incorporate the highest frequency words for greatest linguistic coverage.

But they are, regrettably, also killing student (and teacher) interest and engagement, because the set curriculum is…OK I’ll say it: mind-numbingly boring. Set curricula often ‘covers’ static and humorless topics about which the students are not interested or passionate; nor do many of the themes incorporate the highest frequency words for greatest linguistic coverage.

As we careen toward פסח and then to the end of another Hebrew school year, I’ve transitioned from my role as teacher trainer and lesson modeler, to coach and mentor. I enjoy observing and providing positive feedback to my colleagues as they experiment with their newly adopted teaching with comprehensible input (T/CI) strategies, and I continue to learn so much about how to support both our students’ Hebrew acquisition, and our teachers’ acquisition of the T/CI skills!

As we careen toward פסח and then to the end of another Hebrew school year, I’ve transitioned from my role as teacher trainer and lesson modeler, to coach and mentor. I enjoy observing and providing positive feedback to my colleagues as they experiment with their newly adopted teaching with comprehensible input (T/CI) strategies, and I continue to learn so much about how to support both our students’ Hebrew acquisition, and our teachers’ acquisition of the T/CI skills!

and when possible, add a gesture and/or use a prop to help support understanding. And don’t forget, for our novice learners we can choose to substitute an oral instruction for an extra-linguistic prompt, as in gestures & facial expressions, which can be combined with props, pictures and sketches.

and when possible, add a gesture and/or use a prop to help support understanding. And don’t forget, for our novice learners we can choose to substitute an oral instruction for an extra-linguistic prompt, as in gestures & facial expressions, which can be combined with props, pictures and sketches.